When to Use Wire Rope, Chain, or Synthetic Slings

What are the rules for using different materials for lifting loads and when should I use one over the others?

By Henry Brozyna | Jan 01, 0001

In all the years that I’ve been involved with rigging, this question comes up very often: “when should I use wire rope vs. chain vs. synthetic slings?” There are a few questions here with several answers, so I’ll break this down by question. Before getting into which to use and when, we need to address rules and safety standards.

What are the rules for using different materials for lifting loads?

What are the rules for using different materials for lifting loads?

There are rules or standards for the design, use, care, and inspection of various slings. The standards I refer to include ASME B30.9, WSTDA-RS-1, RS-1HP, WS-1, WRTB as well as OSHA 1910.184, which is a governmental agency.

Let’s get a little history on who these groups are.

OSHA: Occupational Safety and Health Administration

OSHA’s first task, in 1971, was to assemble a staff, and following its congressional mandate, to adopt federal standards and voluntary consensus standards in place at organizations such as the American National Standards Institute, the National Fire Protection Administration, and the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists.

Congress gave OSHA two years to put an initial base of rules in place by adopting these widely recognized and accepted standards. Other standards were to be issued through notice and comment rulemaking.

Since the establishment of OSHA in 1971, workplace fatalities have dropped 60 percent and occupational injury and illness rates have decreased 40 percent.

ASME: American Society of Mechanical Engineers

ASME was founded in 1880 to provide a setting for engineers to discuss the concerns brought on by the rise of industrialization and mechanization.

The Society’s founders included prominent machine builders and technical innovators of the late nineteenth century; led by prominent steel engineer Alexander Lyman Holley, Henry Rossiter Worthington, and John Edison Sweet.

Holley chaired the first meeting, which was held in the New York editorial offices of the American Machinist on February 16th, with thirty people in attendance. From this date onward the society ran formal meetings to discuss the development of standard tools and machine parts, as well as uniform work practices. It wasn’t until 1905 that a major turning point gave new definition to ASME’s purpose and impact on civilian life.

WRTB: Wire Rope Technical Board

The Wire Rope Technical Board (WRTB) is an association of engineers from companies that account for more than 90% of the wire rope produced in the United States. It has the following objectives:

- To promote the development of engineering and scientific knowledge relating to wire rope

- To assist in establishing technological standards for military, governmental, and industrial use

- To promote development, acceptance, and implementation of safety standards

- To help extend the uses of wire rope by disseminating technical and engineering information to equipment manufacturers

- To conduct and/or underwrite research for the benefit of both industry and user

The Web Sling & Tie Down Association (WSTDA)

The Web Sling & Tie Down Association (WSTDA) is the largest non-profit, technical organization dedicated to the safe operation of all synthetic web slings and tie downs. Comprised mostly of sling and tie down manufacturers, WSTDA membership also includes fiber suppliers, weavers, testing companies, government enforcement agencies, and other interested parties from countries around the world. WSTDA is recognized internationally, with members from the United States, Canada, Mexico, Europe, and Asia.

The WSTDA’s core mission is the development and promotion of voluntary Recommended Standard Specifications covering the most common synthetic web lifting and tie down products. The current Standards cover construction, selection, use and maintenance of Synthetic Webbing, Thread, Web Slings, Round Slings, Tie Downs, and Chain Binders.

The WSTDA has been a trusted resource since its formation as the Web Sling Association in 1973 and is recognized by the U.S. Department of Justice as a Standards Writing Organization.

So, long story short, are there rules for using different materials for lifting? Yes, there are.

All industrial groups have volunteers that sit on various committees to establish these standards. OSHA can use standards through what is called the General Duty Clause CFR 29-USC 654. By using this General Duty Clause, OSHA can use the standards in a court of law and they can be binding. The use of CFR 29 has a long-established history of precedent in our legal systems.

Now for the answer we’ve all been waiting for:

When to use wire rope, chain, or synthetic slings?

Now when should a rigger use a particular type of sling? The answer isn’t so straightforward. Oftentimes it will depend on what the rigger has available at the time of the lift.

Each sling type does have its advantages as well as disadvantages. Let’s look at some of the differences.

Wire Rope Slings

Wire rope is made of metal, making it very durable with higher working load limits. Metal can also be very heavy when working with larger sling sizes. The metal design requires lubrication, which can be done properly by following the manufacture's recommendations for what type of lube to use and the proper procedure for lubrication.

Wire rope can have an Independent Wire Rope Core, IWRC, or it can have a synthetic core. Matching up size for size, the IWRC will offer a higher working load limit when compared to synthetic core.

IWRC rope is not as flexible as its synthetic core counterpart. This is important to know if you plan to wrap the wire rope around a load or go around a tight corner. If this consideration is not observed, the wire rope may permanently kink once loaded, damaging the rope and requiring it to be removed from service. Always keep in mind wire rope's flexibility limitations when considering sling type.

When it comes to damage in a wire rope sling, refer to ASME B30.9. A wire rope sling can have some broken wires and still be acceptable for use. ASME B30.9 states that there can up to ten randomly distributed broken wires in one rope lay, or five broken wires in one strand in one rope lay.

In all my years in the industry, kinks and lack of lubrication top the list for wire rope rejection.

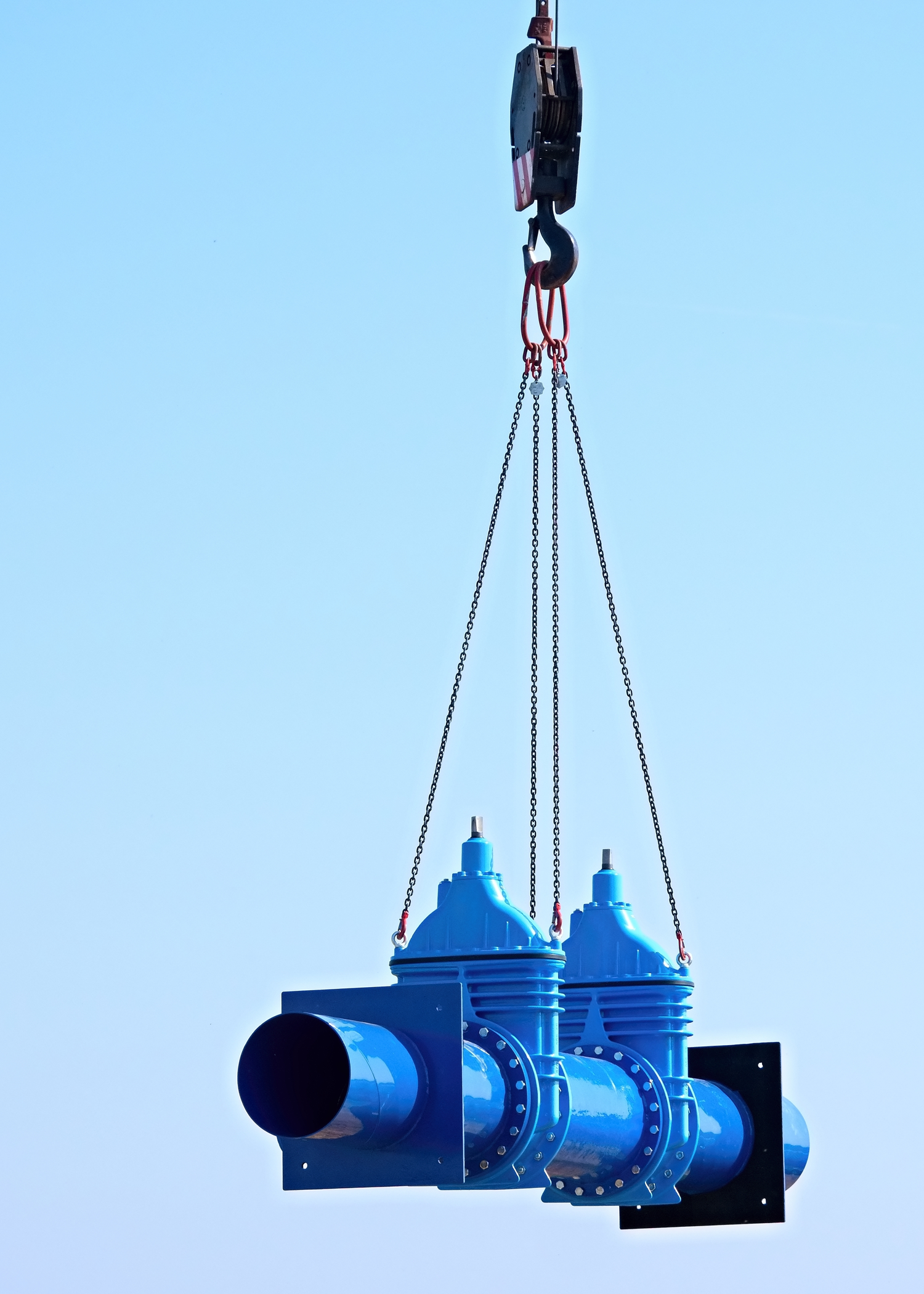

Chain Slings

Chain is made of metal and like wire rope, is very durable with high working load limits. It can be heavy in the larger sizes and requires lubrication, following manufacturer recommendations for care and lubrication guidelines. Chain can have some damage and still safely lift loads. Consult the ASME B30.9 standards or OSHA 1910.184 for more information.

Chain is very flexible and can handle corners with greater ease than wire rope. This does not mean that corners of loads can be ignored when lifting with chain slings. As with wire rope, rounding a tight corner can damage the chain, so always consider the lift design and trajectory prior to your lift.

When it comes to chain, the main issues I've experienced include lack of training, improper use, and improper care. These can lead to property damage and personal injury.

Synthetic Slings

Synthetic slings are made of synthetic fibers, much like the clothes you’re wearing right now. These materials have a very high strength to weight ratio. They don’t require lubrication like metal slings, but aren’t as durable. Since all synthetic sling fibers are load bearing, any damage requires the sling to be removed from service (see ASME B30.9 & OSHA 1910.184).

Synthetic slings shouldn’t be used to lift loads in elevated temperatures as they may melt or burn. If handling loads at high temperatures, opt for chain or wire rope.

As with chain and wire rope slings, synthetic slings have restrictions regarding how tight of a corner they can navigate. If you are working with a synthetic sling that has multiple layers stitched together, tight corners risk breaking those stitches.

Main synthetic sling issues come down to improper care and continued use of damaged slings. If a sling has cuts, snags, missing labels, tears, or holes, they need to be removed from service immediately. This unfortunately common mistake will lead to injuries and property damage.

So what should I use?

In most cases it depends on the rigger’s preference and what equipment they have on hand. If you’ve been in the industry as long as I have, you’ll come across some loads that warrant a specific type. At that point, I always recommend following the manufactures recommendation.

For most loads, sling type selection is up to the rigger and depends on how the load is to be lifted. In some instances, it is obvious one type of sling would be better than another.

Sling selection covers a very small portion of your pre-lift considerations. It’s a best practice to create a complete lifting plan for every lift, taking the time to consider the safest and most efficient way to move your load.

Henry Brozyna

Henry Brozyna is an Industry Product Trainer at Columbus McKinnon specializing in Crane and Hoist Inspection and Repair, Rigging & Load Securement He has been training on crane and rigging safety for more than 20 years. Henry is a member of the Tie Down committee and former Board of Directors for the WSTDA; this group writes the standards that are used by the material handling industry, the transportation industry, and also law enforcement. Henry is also a current member of the Crane Institute’s board of directors.

North America - EN

North America - EN